[Research]

Using Mixed Methods in Music Therapy Health Care Research: Reflections On the Relationship Between The Research Question, Design and Methods in the Research Project Receptive Music Therapy With Female Cancer Patients in Rehabilitation[1]

By Lars Ole Bonde

Abstract

“Mixed methods” (or “multiple methods” or “multiple strategy”) research design is a fairly new concept in music therapy research. It is inspired by recent methodological developments in the social sciences, covering the interaction of quantitative and qualitative methods in one and the same research study. Mixed methods are not the same as the diversity or pluralism of methods advocated by many scholars who are critical towards the principles of evidence-based practice. This article presents an example of mixed methods in music therapy research: a psychosocial study of music therapy with female cancer survivors. Problems related to ontology, epistemology, design and methodology are illustrated and discussed, and the perspective is broadened into a discussion of the core concepts of triangulation as related to validity.

Keywords: cancer, rehabiltation, mixed methods.

Prelude

Mrs. M. participated in a research project, attending music therapy one and a half months after discharge from hospital for the treatment of breast cancer. Her baseline pre-test score on a quality of life dimension in the intake questionnaire was 7; on a scale with anchors titled 1 (very poor) to 7 (very good). In a follow-up interview, she explained her surprisingly positive baseline result in this way: “I was not asked questions like ‘How many times during the last weeks have you been really down?’ The instruction said that the answer should only address the last week, in which I felt fine, and it was not possible to report feelings of ‘depression’ that I had in the week before that.” Later in the interview I asked her: “According to two of the questionnaires the music therapy had no effect for you. But now you tell me that it did?!” Mrs. M.: “Yes, it has been... well if not the most important outcome in my whole life, then at least in the later part of my life. That’s for sure.”

In other words: at the time of the pre-test score, Mrs. M. was free of pain and reported her quality of life as maximum at baseline. 6 months later, at follow-up (6 weeks after post-test and the last music therapy session) Mrs. M. scored her quality of life at 6 on both questions. From an empirical viewpoint she indicated a deterioration following music therapy. The interview however, told another story. In the interview Mrs. M. indicated that the music therapy experience had a profound impact on her life. The only way she could express this in the questionnaires was to add personal comments in the margin. For example, she answered the query in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HADS) questionnaire: “Do you enjoy things as much as you did before?” with the highest score “as much as before”, but she also included some comments written in the margin: “even more than before”, and “I also enjoyed new things”.

Introduction

In this article, I will describe mixed methods research, [2] using my research with cancer survivors (Bonde 2005a) as an exemplary illustration of mixed methods research (Aigen, 2008a) and as an example from which to address the many problems related to ontology, epistemology, design and methodology that are raised vis-à-vis mixed method research. I will outline my research project briefly as background for a discussion of some of the issues related to the interplay of research question(s), design and methods. Selected results are highlighted with a focus on advantages and disadvantages of combining standardized questionnaires with qualitative interviews. In the discussion, I will include some general reflections on the rationale of using mixed methods as well as a discussion of core concepts in the study. I will present some critical issues emerging from the evaluation of the study, in order to broaden the perspective, and finally I will discuss the question of mixed methods, validity and generalization, including some reflections on ‘truth’ in health care research.

A Rationale for Using Mixed Methods

I classify myself as a humanistic researcher, as I, as a musicologist, was trained in the qualitative traditions of hermeneutic inquiry and critical theory. I have published many purely qualitative studies in music education and music therapy. When teaching music therapy students theory of science, including the question of paradigms and methodologies, my explicit stance has always been that "quantitative and qualitative are not scientific paradigms, but complementary research methods", and that the choice of design and methods should be determined by the nature and formulation of the research question:

When determining the paradigm that is most appropriate, it is far more relevant to establish the focus of the research question first, before deciding on an appropriate research method. (Wigram, Pedersen & Bonde, 2002, p. 225)

This standpoint is – at least in principle – in accordance with de Vaus (2001), who writes that the research question should determine the formulation of the design and guide the choice of methods.

However, there are other contextual reasons that someone might choose mixed methods research. From a pragmatic point of view, mixed methods is useful for music therapists working in multi-disciplinary teams, especially in contexts where a combination of descriptive statistics, phenomenological descriptions and hermeneutic interpretations is relevant. In the present era of Evidence Based Practice (EBP), music therapists are often expected and required to document the effect of their treatment in explanatory research, preferably in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (Ansdell & Pavlicevic 2001; Wigram & Gold 2012)[3]. However, it is very difficult to design RCTs in music therapy, as in other forms of psychotherapy, and music therapists have in most cases not been trained to perform research within this advanced medical tradition[4].

Sometimes, the context calls for the use of quantitative methods (for example, for funding purposes), even if the research question points towards qualitative research methodology. In my doctoral study of music therapy with female cancer survivors in rehabilitation, one important purpose was to establish contact and communication with professionals in the Danish health care systems, or more specifically professionals in oncology, that is, doctors, nurses and consultants. Based on preliminary dialogues with some of these professionals, and on the demands and standards of funding agencies, I realized that a purely qualitative study would not open any doors in Danish hospitals or rehabilitation centres to music therapists. In order to establish a dialogue it was inescapable to include a quantitative dimension to my study. Thus, I was faced with several challenges and dilemmas: Not only would I have to develop skills in statistics and quantitative methods; I would also have to consider the relationship between my basic beliefs as a researcher, my research background, interests and questions, and the implications of designing a study including quantitative methods. Consulting relevant literature on research methods in social science and in music therapy I met conflicting views.

On the positive side, Robson (2011) maintained that the scientific world is in a multi-paradigmatic stage, and there is almost never only one method to answer a specific research question, even if there can be specific expectations to the researcher (Robson, 2011, p. 25). However, the three major research cultures of 1) natural science, 2) social science, and 3) humanistic science, still have a tendency to emphasize certain research strategies and evaluation standards, based on very different criteria. Qualitative research is still a rare approach in natural science, and quantitative research is still only a niche in humanistic science. The broadest scope of research approaches is found within social science. Social scientists have developed a wide spectrum of designs and strategies, including both quantitative and qualitative methods, and reflections on when, why and how to combine methods. This is reflected for example in the title of Creswell (2003): Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches.

Robson (2002, 2011) suggested that the terms fixed vs. flexible design could be a more appropriate way of understanding the relationship between paradigm and methods. He also supports the use of mixed methods (or, as they are called in the 2011 edition: “multi-strategy designs”): “Using more than one [method] can have substantial advantages, even though it almost inevitably adds to the time investment required” (Robson, 2002, p. 370). The epistemological advantages may be 1) the reduction of inappropriate certainty (nice, "clear-cut" results may not be "right"); 2) mixed methods permit triangulation (of sources, methods, investigators, or theories); 3) they may be used to address different but complementary research questions within one study; and 4) they may enhance the interpretability of the results. Robson has summarized 11 ways in which qualitative and quantitative methods can be combined. Many of these combinations can be found in the present study, which I, (as a whole, using Robson’s terminology) consider a qualitative research study based on a flexible research design including quantitative methods. When I was preparing the study, I was not aware of de Vaus’ influential work and position (de Vaus 2001), however, I will include some of his ideas in the discussion section.

Mixed Methods in Music Therapy Research

In a review of the music therapy literature from 1987-2006, Aigen (2008a, 2008b, with an unpublished update in 2012) identified 26 mixed methods studies published as journal articles or book chapters, while the number of mixed methods doctoral studies in the same period was 12. In the doctoral program at Aalborg University, where I work and supervise, mixed methods studies have become increasingly popular since the first study of that type was defended in 2003 (Ridder, 2003). Ten PhD Theses (defended between 2005 and 2014) using mixed methods can be downloaded from http://www.mt-phd.aau.dk/phd-theses/.

However, the music therapy literature on mixed methods is not comprehensive. The topic was not included in the first edition of Music Therapy Research (Wheeler, 1995), and in the second edition (Wheeler, 2005) it is only addressed briefly in one chapter (Wheeler, 2005a). It is significant that in the third edition (Wheeler & Murphy, in press) there is an entire unit (three chapters) devoted to mixed methods designs. Edwards (1999, 2005) emphasizes the importance of explicating epistemological and ontological considerations of the researcher, relying less on overarching methodological concerns (such as qualitative and quantitative), more on underpinning the researcher’s beliefs and their influence on the choice of method. The first overview article – apart from my own limited contributions (2007d, 2007b) – on mixed methods (MM) in music therapy research was published in 2013 (Bradt, Burns & Creswell, 2013). This article includes an overview of the worldviews (paradigms) behind MM research, a short history, a review of four basic designs in MM (the convergent parallel design, the explanatory sequential design, the exploratory sequential design, and the embedded design), criteria for evaluation and recommendations for the application of MM to music therapy research. It also includes a review of three MM studies from the period 2010-12, representing different research designs. All this indicates that MM studies have become more common, and that we are moving away from the old polarization of quantitative and qualitative methods understood as epistemologies, cultures, or paradigms[5] - the no longer tenable “incompatibility thesis” as Robson (2011) calls it.

The next two sections provide a short overview of my own doctoral study applying mixed methods (Bonde, 2005a). Research questions, design, method and results are briefly outlined, followed by a closer look at some of the quantitative results.

A Music Therapy Study Using Mixed Methods

The Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music (GIM) with Cancer Survivors: A Psychosocial Study – Questions, Design, Methods, Results

Clinical method: The Bonny Method of GIM was developed by Helen Lindquist Bonny and is the internationally most used receptive music therapy model. It can be defined as "a model of music psychotherapy centrally consisting of a client imaging spontaneously to pre-recorded sequences of classical music" (Abrams 2002, pp. 103). Or in other words: it is receptive music therapy, based on music listening in an interactive dyad format. A session last app. 90 minutes, with about half of the time devoted to music listening and imaging in a relaxed state.

The participants were 6 women, 40-65 years old, in cancer rehabilitation (1,5 to 18 months after discharge from hospital) who volunteered to receive 10 biweekly, individual Bonny Method sessions conducted by a certified GIM therapist. The setting was the standard session format (prelude-induction-music travel-return-postlude; Bonny 2002), and the standard GIM music repertoire (programs and selections of classical music) was used.

Main question: What is the influence of ten individual GIM sessions on mood and quality of life in cancer survivors? - Sub-questions:

- Can ten GIM sessions improve the mood of the participants?

- Can ten GIM sessions improve the quality of life of the participants?

- Can music and imagery help the participants in their rehabilitation process?

- What is the experience of the participants of GIM and its influence on mood and quality of life in the rehabilitation process?

- What is the specific nature of the imagery/image configuration of cancer survivors?

- How does the imagery develop and/or get re-configured during GIM therapy?

- What elements are there that describe the relationship between the music and the imagery transformations?

Design

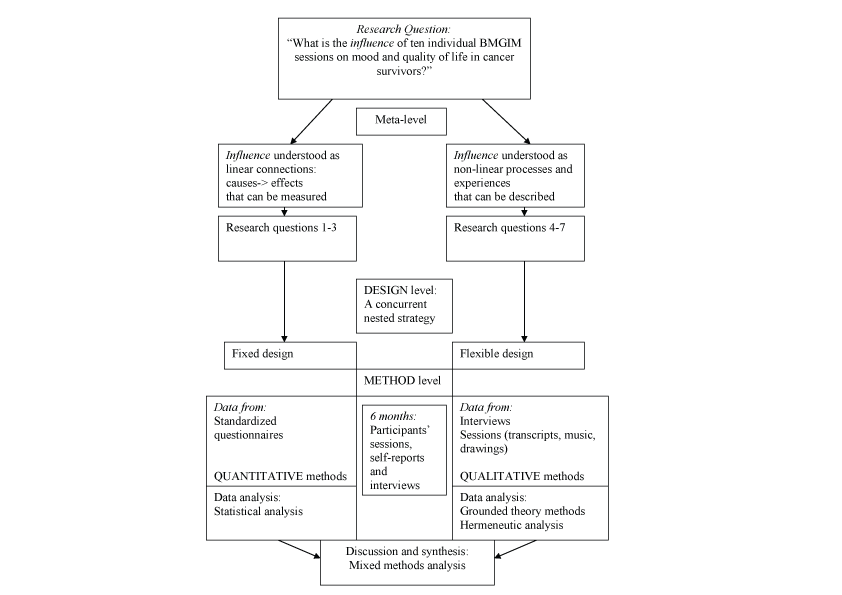

The study was designed, using Robson’s terminology, as “a flexible research design study, including quantitative methods.” Using Creswell’s terminology it could be called “a concurrent nested strategy” (Creswell 2003, p. 218; Robson, 2001, p. 165): there is one quantitative data collection phase, but given less priority, the quantitative method is embedded and addresses a different question than the dominant qualitative method. A graphic overview of the design is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Graphic overview of the research design. [Full size image]

Figure 1. Graphic overview of the research design. [Full size image]

Subquestions 1-3 were addressed in a quantitative investigation with 10 hypotheses. Subquestions 4-8 were addressed in a qualitative investigation in three parts: 1. With focus on the participants’ experience of the GIM therapy, 2. With focus on the imagery, 3. With focus on the interrelationship between music and imagery.

MethodsThe quantitative investigation was a clinical trial/pre-post-follow-up-design/ multiple case study design. Focusing on the experience of anxiety, depression and quality of life that are considered basic problems in psycho-oncology, the following questionnaires/self reports were used in the data sampling:

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Snaith & Zigmond, 1994) in addition to (a1) four specific music therapy questions (in the same format)

- European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) (Fayers, Weeden et al. 1998)

- Antonovsky's Sense of Coherence Scale (SOC) (Antonovsky,1987)

Data points. after every session questionnaires (a) + (a1) + (b) were filled in. After termination and 6 weeks later all questionnaires were filled in. 2-4 weeks after follow-up all participants were interviewed by the researcher.

The qualitative investigation had five elements:

Results

- Grounded theory analysis of interviews with the six participants after follow-up,

- Grounded theory analysis of images and metaphors evoked in all (60) sessions,

- Two in-depth case studies – a hermeneutic/mimetic analysis of the imagery and its development in two participants,

- Event structure analyses of the interrelationship of music and imagery in four music selections that were used with minimum four participants.

- Grounded theory inspired categorization of the music used in the project.

The quantitative investigation. Inferential statistics (Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test) and effect sizes were calculated on (selected) scores of the three questionnaires. A significant difference was found pretest to follow up on the anxiety subscale of the HADS (p = ,045, ES = 1.33). No significant difference was found for the EORTC QLQ-C30. A significant difference was found pretest to posttest on the SOC (p = ,028; ES = 0.62) and pretest to follow-up (p = ,027; ES = 0.41).

The qualitative investigation. In the analysis of the semi-structured interviews with the six participants the following core categories emerged as descriptors of their GIM experience: Enhanced coping, Improved mood, New perspectives on past/present/future, Enhanced Hope, Improved self understanding, Coming to terms with life and death, Opening towards spirituality (for details see Bonde, 2007a, 2007b).

The imagery of the participants was analysed, based on the principles of (1) grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1995) and (2) hermeneutic investigation (Ricoeur, 1978, 1984) The analyses showed that core metaphors and self metaphors emerged with all six participants, and that configuration of metaphors in narrative episodes or longer, coherent narratives could be identified in 5 of the 6 participants (see Bonde, 2005, 2007a, 2007c).

The interrelationship of music and imagery was analysed. Three types of music with specific therapeutic properties were identified: “Supportive music”, “Challenging music” and “Mixed supportive/challenging music” (for a detailed presentation of this typology, see Wärja & Bonde, 2014); and a grounded theory on the therapeutic function of music in BMGIM was suggested (see Bonde, 2004, 2007a, 2007c). An in-depth investigation of one participant’s GIM process was published as a case study (Bonde 2005b).

A Closer Look at the Quantitative Results

Anxiety

In HADS, anxiety is defined as a concept covering “the general state of anxious mood, thoughts, and restlessness” (Snaith & Zigmond, 1994). This operational definition allows the researcher to ask specific sub-questions, measure the self-perceived level of anxiety and perform a pre-post-test. Participants answer 7 questions on a 4-point Likert scale within a spectrum from Not at all to Very much (or similar). The total score is placed in one of four groups: Normal (0-7); Mild (8-10); Moderate (11-14) Severe (15-21).

Figure 2 shows the development in the anxiety scores of the participants from pre-test to follow-up. A clear normalization over time can be observed in all 6 participants.

Depression

In HADS, depression is defined as “the state of loss of interest and diminished pleasure response (lowering of hedonic tone)”, and it is operationalized in the same way as anxiety (Snaith & Zigmond, 1994). Figure 3 shows the development in the depression scores of the six participants.

Figure 3 shows the development in the depression scores of the participants from pre-test to follow-up. The scores were low already at pre-test, and all six participants were in the normal range at post-test.

Quality of Life

In EORTC QLQ-C30, quality of life is not defined, but it is covered by two questions: ’How do you rate your global health / quality of life?’ Participants answer on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from Very poor to Excellent. In the study, there were no clear patterns in how participants answered the two questions at the three measure points.

Sense of Coherence

Antonovsky (1987) developed his theory of Sense of Coherence (SOC) and the related questionnaire to capture a multi-dimensional understanding of health as a synthesis of three experience components: comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness (Antonovsky 1987). Figure 4 shows the SOC scores of the six participants.

Three participants showed remarkable improvements in their SOC scores, while the other three were almost unchanged (and had their scores been just one point lower at post and follow up than at pretest, there would have been no statistically significant differences). However, in the interviews with the three participants whose scores were almost unchanged it became clear that they had experienced psychological development and quality of life improvements during music therapy (like Mrs. M’s quotes in the Prelude of the article).

In the interviews, and also during the therapeutic process, the participants had many critical remarks about the limitations of the questionnaires. Here are some examples of this critique, highlighting problems of both validity and reliability:

Mrs. J.: “One week may include many ups and downs - this cannot be indicated when ‘ticking a box’ about ‘the last week’ is the only option.”

Mrs. M.: “The questionnaires may not show it, however, music therapy has had the greatest impact on quality of life in the later part of my life!”

Mrs. L.: “What I find so difficult about these questionnaires is that the changes I have experienced cannot be attributed to any single influence. I know definitively that the apparent ’lack of change’ in my scores [of which she was informed] was also influenced by my negative attitude towards them...Another thing is that I am sure I would have felt worse and might have scored lower on several items, had I not participated in this project... I have become more conscious about some of the more tiresome or difficult things in my life.”

Discussion

Validity of Core Concepts: Anxiety, Depression, Quality of Life

In this study, I originally wanted to use the same standardized questionnaires that Burns used in her small-scale RCT (Burns, 1999, 2001) to assess mood and quality of life, namely the Profile of Moods Scale (POMS) (McNair, Lorr et al., 1971) and the Quality of Life – Cancer Patients questionnaire (QOL-CA) (Padilla, Grant et al., 1996). However, discussions with oncologists in Denmark and Sweden on the choice of questionnaires made it clear that there are different preferences in the US and Scandinavia – so other questionnaires were recommended: the HADS (for mood) and the EORTC-C30 (for quality of life and side effects). The SOC was also included because it has been used in related GIM research (Körlin & Wrangsjö 2001, 2002), and the salutogenic perspective on health (Antonovsky, 1987) is related to quality of life. No matter which questionnaire is chosen, the researcher must reflect on other ways of understanding them, especially when the core concepts denote more than specific side effects or pathological symptoms they were designed to address. The core concepts of my study illustrate this clearly.

Anxiety. Anxiety as defined in HADS - was experienced as normal, mild or moderate by the participants, and their scores normalized during therapy. However, as Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard stated, anxiety is a basic human condition (what he called a constituent characteristic of the human being), it is object-free, at the core of existence and, as such, is not a pathological symptom at all.

Depression. Depression as defined in HADS – did not seem to be an important issue for the participants, and their scores were low already at pre-test. In contrast, in existentialism depression is not understood as a "disorder", but as a natural, human reaction to, for example, a life crisis, such as facing mortality, experiencing lack of meaning, or feeling abandoned. The participants certainly struggled with such reactions to living with cancer.

Quality of Life. In contemporary health psychology, quality of life is defined as a multi-dimensional concept, including issues such as emotional awareness, sense of agency and belonging, life experienced as having meaning and coherence (Ruud, 1998). This complexity was not included in the two simple questions of QLQ-C30. However, the SOC questionnaire addressed and reflected the complexity.

In other words, standardized questionnaires are always reductionist, mostly a-theoretical and they can only cover very limited and uni-dimensional aspects of a phenomenon. Therefore, it is understandable that some participants find them not only reductive, but also vague and inaccurate and that they may prefer methods enabling them to be more specific about their experiences. The use of mixed methods enables a wider exploration of complex concepts and makes it acceptable that self-reports only allow limited answers to complex questions. The combination of self-reports and qualitative interviews gives the participants the opportunity to formulate their critiques and ideas, and the researcher an opportunity to elaborate his/her own understanding of the issues and concepts operationalized in the questionnaires.

Based on my experiences in this and other mixed methods studies, I consider the combination of self-report questionnaires and semi-structured interviews a methodological advantage. Even if some of the six participants in the study had many reservations and critical remarks to the validity and reliability of the questionnaires they all did acknowledge their scores in the questionnaires as a valid source of information on aspects of their process and outcome.[6]

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Design

The advantages of the flexible research design or the concurrent nested strategy in this study can be summarized as follows:

- The design ensured that a voice was given to the participants.

- Questionnaires and interviews were a good combination in practice.

- The design ensured results enabling a dialogue between research cultures and their representatives.[7]

- The design ensured results contributing to the foundation of Evidence Based Practice (EBP) in the field.

However, consideration should also be given to potential disadvantages such as:

- The design does not compensate for reliability and validity problems related to sample size and recruitment. (Small samples and absence of a control group make less credible evidence that cannot be compensated for by in-depth qualitative analyses).

- The design does not prevent that questionnaires can be experienced as artificial or irrelevant by participants (standardized self-reports may not always work meaningfully together with qualitative interviews) or that the use of interviews can be considered biased by some researchers.

- The design (and the combinations of methods, and/or the reporting style) may not be accepted by evaluators, reviewers and editors.

Of course, the design used in this study did not solve the obvious problems of validity related to the small sample and the lack of a control group. The participants in the study may have had a special motivation influencing the results in a positively biased way, and this issue was not accounted for in the design. However, the quantitative results made it possible to compare results from this study with results from other studies and relevant reference groups. I think this is a very important dimension of using mixed methods in studies of psychosocial interventions.

Critical Ontological and Epistemological Issues

The study raised several meta-theoretical problems of potentially conflicting paradigms and methodologies. I will address these problems through a clarification of my axioms, my paradigm, my choice of design, and my understanding of using mixed methods in one study.

Critical questions that have been raised about this study concern what is meant by evidence, whether it focuses on outcome or process, and a (mis)understanding of qualitative and quantitative methods as being epistemologically mutually exclusive. If the purpose of this study is seen as outcome based, and based on causal thinking, it is seen as adhering to a (post)positivist paradigm. However, I understand this study as looking “at how cancer patients in rehabilitation experienced GIM therapy and how it influenced the rehabilitation process” (Bonde, 2005a, p. 119). I described the study as “a flexible research design study, including quantitative methods in order to a) cover a ‘structural’ aspect of the phenomenon (outcome), b) permit a certain degree of statistical generalizability, c) combine the micro-level of individual processes with the macro-level of norms and standards, d) enable a discussion on outcome with the participants, and with colleagues from other health professions” (p. 123). Thus, how could this—and the overall design of the study—be identified with a (post)positivist paradigm? For those who see it in this way, it may be related to: (1) Certain properties of the dissertation, such as the carefully differentiated reporting styles (in chapters on the quantitative versus chapters on the qualitative investigation); (2) An incomplete or insufficient explanation from my side of the design as developed from the research question; or, (3) Different interpretations of a central concept used in the basic research question. I will address these problems one by one.

1. In the dissertation the results of the quantitative investigation were reported in one chapter (33 pages), written in the traditional style of natural science and taking the subquestions/hypotheses one by one. The results of the qualitative investigation were reported in 3 chapters (145 pages), written in different styles related to the specific methods applied to the subquestions. This differentiated reporting style was chosen very consciously, as it is recommended by Robson. However, even a limited number of graphs and tables may confuse some readers to think that this was primarily a study based on (post)positivist notions.

2. The methodology was explained stating: “Based on the nature of the research questions, this study employs multiple methods, and includes both fixed and flexible design” (Bonde, 2005a, p. 119). After this, a section is devoted to the discussion of epistemological challenges in using mixed methods/multiple methodology. In my original reporting of my study, I may not have been clear enough in explaining how the design grew logically out of the research questions (as illustrated in the flowchart, Fig. 1), and that I have used the concepts “mixed methods/multiple methodology” almost as synonymous with “design” in the meta-theoretical discussion. De Vaus’ clear delineation of the sequence research question – design – method would have been very useful here.

3. The basic research question was "What is the influence of ten individual BMGIM sessions on mood and quality of life in cancer survivors?" “Influence” is the key word. It has paradigmatic connotations, therefore I will have a closer look on the etymology of the word and then give my rationale for using it. “Influence” is not the same as “effect”, and it does not imply “causality” and linear thinking. In my understanding of the word (and its meaning) it is a metaphor, an ambiguous conceptualization of a process where (in this case) music therapy flows into the bodies, minds and spirits of six cancer survivors. The influence concept was chosen deliberately with the intention of making the research question open and inclusive, in other words: it should not indicate any specific paradigm or research method.

The question was then broken up into the two main meaning components of the concept: a more (post)positivist concerned with causes and effects, requiring a fixed methodology (to deal with sub-questions 1-3), and a more constructivist concerned with processes and experiences, requiring a flexible, emerging methodology (sub-questions 4-7). Terms that are traditionally associated with quantitative research and postpositivism, such as “effect”, “outcome”, “causality”, “evidence” and “significance” can be used within qualitative research, and postpositivist designs, but with different meaning. Such differences in meaning must however be made very clear and sturdy when using mixed methods (Bradt et al., 2013; Robson, 2011).

This design, leading to the use of mixed methods reflects my understanding of the multi-paradigmatic nature and present situation of music therapy research, not a wish to mix paradigms or create an epistemologically naïve combination of methods. My basic philosophical stance is constructivist/reflexive. As a human endeavour music (and the music experience) is a multi-layered phenomenon, not either a case of stimulus-response or an experiential paradigm (Bonde, 2009). Thus, in my understanding, the research project was neither a study based on a (post)positivist paradigm, nor split in two halves with separate paradigms, it utilised an eclectic approach. I use the word ‘eclectic’ in the same way as Ferrara (1991) uses it when characterizing his method of music analysis: Music is Sound, Structure and Meaning[8]. This reflects the way in which each aspect or level of the research demands a specific methodological approach. Køppe (2012) presents a thorough theoretical discussion of onotological and epistemological issues related to eclecticism, and he argues that a moderate eclecticism is an important component in contemporary scientific development.

Paradigmatically and epistemologically I share Lakoff and Johnson’s ideas about causality, as they are unfolded in “Philosophy in the Flesh” (Lakoff & Johnson, 1999). In their book, the authors present many distinct conceptualizations of causation, each with a different logic. (p. 171). The – (post)positivist – prototypical case: the manipulation of objects by force is only one of many cases of causality. Metaphorical concepts of causation may provide a much richer source of causal reasoning.

…the literal skeletal concept of causation: a cause is a determining factor for a situation, where by a “situation” we mean a state, change, process, or action. Inferentially, this is extremely weak. All it implies is that if the cause were absent and we knew nothing more, we could not conclude that the situation existed. This doesn’t mean that it didn’t; another cause might have done the job. … (Lakoff & Johnson, 1999, p. 177)

Robson (2002, 2011) also discussed the issue of "causality" in (post)positivist vs. non-positivist paradigms. An axiom of (post)positivism (based on Hume’s theory of causation) is that “Cause is established through demonstrating such empirical regularities or constant conjunctions – in fact, this is all that causal relations are.” (Robson, 2002, p. 20). This positivist, successionist view on causality is challenged by the realist, generative view, where qualitative analysis can be a powerful method for accessing causality, understood as the identification of “mechanisms, going beyond sheer association. It is unrelentingly local, and deals with the complex network of events and processes in a situation. It can sort out the temporal dimension, showing clearly what preceded what, either through direct observation or retrospection. It is well equipped to cycle back and forth between variables and processes – showing that ‘stories’ are not capricious, but include underlying variables, and that variables are not disembodied, but have connections over time.” (Robson 2002, p. 475, the quote is from Miles and Huberman (1994) Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd edition.) In this quote, including several words normally associated with a (post)positivist paradigm, I find several characteristics reflecting the properties and intentions of my own project, where the influence concept is meant to cover a broader understanding of causality than merely empirical regularities. But what becomes of validity, and how can triangulation be used?

Mixed Methods, Validity and Triangulation

Bruscia (1995) wrote about what he then considered the music therapy researcher’s “unavoidable dilemma”:

Notwithstanding the possibility of collecting both quantitative and qualitative data in the same study, and combining the different interests and methodologies, the two philosophical paradigms cannot be integrated or combined. They are mutually exclusive ways of thinking about the world” (Bruscia, 1995, p. 73)

Bruscia’s standpoint was very influential in the early debate on paradigms and methodologies in music therapy research, and in the early 90’es there was a tendency in the music therapy research community to divide into two camps who were mutually exclusive – what Aldridge (1996, p. 278) called ”methodolatry”[9].

In this view, triangulation is only accepted within a paradigm (equated with methods). However, there are other options. Mason (1996) presented a different understanding of triangulation, closer to my own standpoint:

At its best, I think the concept of triangulation - conceived as mixed methods - encourages the researchers to approach their research questions from different angles, and to explore their intellectual puzzles in a rounded and multi-faceted way. This does enhance validity, in the sense that it suggests that social phenomena are a little more than one dimensional, and that your study has accordingly managed to grasp more than one of those dimensions. (Mason, 1996, p. 149; in Meeto & Temple, 2002, p. 7)

The question of validity and the possibility of triangulation between quantitative and qualitative investigations in one study needs further discussion, and there are no easy solutions (Meetoo & Temple, 2002; Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004). Research is a social activity during which researchers and participants produce a context specific account, and social reality cannot be described unproblematically from one "correct" perspective. In a constructivist (or interpretative or reflexive) view of social reality, the context and conditions under which data have been produced are crucial, and adding together data collected from different methods is therefore problematic. However, comparing results from different methods is of value because social reality is multi-faceted and perspective is all-important. Thus, different methods may be used to verify each other – but they may also be complementary or contradictory.

Conclusion and Postlude

Different methods use different processes to construct findings and these different processes are valuable in contextualising data generated in different ways. For example, one of the benefits of in-depth interviews are that they allow for dialogue and debate around what a concept means, whereas a questionnaire is often a de-contextualized choice of tick boxes. In social life we are often presented with both ways of choosing. Sometimes we have to choose between two fixed alternatives without being able to give the "ifs" and "buts" (Meeto & Temple, 2002, p. 8)

This was certainly the case in the study presented here, and it would not surprise me if the majority of participants in health care studies dislike a limited choice between fixed alternatives. As researchers we can provide a more flexible situation for the participants. We are studying their life world and have an obligation not to treat them as mere ‘informants’ of questions defined by us, the researchers. Such considerations must be included both in the formulation of research questions and in the design of the study. This is why I think mixed methods research has been successful in establishing itself as a ‘third way’ in contemporary health care research, including music therapy. Also when we report our questions and findings the rationale for our choices must be made clear:

Researchers should spell out their research process and their epistemological and social position within their research to enable the reader to actively engage with the arguments being put forward. (Meeto & Temple, 2002, p. 9)

This is echoed by Bradt et al. (2013) who recommend that researchers articulate and discuss their paradigmatic stance. The interests of the participants must also be considered. As I have demonstrated, the women who volunteered as participants in the present study were very engaged, also in the research methodology and reporting style. They readily gave me permission to use not only data from questionnaires and interviews but also transcripts of sessions, mandala drawings, poems and artwork. I have used this permission to include the dimension of art in every presentation of this project, and therefore I will end this chapter with a poem, written by one of the participants and based on her music therapy experiences.

Mrs. M’s poem

On the beach

I watch the ocean

And the waves

I see a wave being born

Roll along

Roll over

Die

Being reunited with the ocean

I see a new wave been born and I ask:

Wave, while you are wave - do you know

That you are also Sea?

I see the ocean

I see the waves

I see myself - a wave

And I know that I am also the sea!

Notes

[1] This article is a revised version of "Using multiple methods in music therapy health care research. Reflections on using multiple methods in a research project about receptive music therapy with cancer survivors" published in Jane Edwards (Ed.), Music: Promoting health and creating community in healthcare contexts (pp. 105-122). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. A version in German, "Kreative Methodenintegration in der musiktherapeutischen Forschung- Reflexionen über Methodenwahl und Methodenprobleme im Forschungsprojekt 'Rezeptive Musiktherapie mit Krebspatientinnen in der Rehabilitationsphase'" was published in Musiktherapeutische Umschau 28(2), 93-109. The present, much longer version was originally planned as a chapter in G. Scott Reinbacker (Ed.) Research Design. Validation in Social Sciences, a book that was never published.

[2] Multiple methods and mixed methods are two often used terms covering the same phenomenon. Robson (2011), uses the term “multi-strategy (mixed method) designs.” In this article I will use the term mixed methods, corresponding with the terminology in Bradt et al. (2013).

[3] A whole issue of the German journal Musiktherapeutische Umschau (2004,3) was devoted to the discussion of the relevance of EBP criteria for music therapy research and clinical practice. See also Bonde, 2007a, 2007b.

[4] However, and reflecting new competencies of music therapy researchers, the Cochrane Library has published a number of protocols on music therapy as an effective treatment.

[5] Ansdell & Pavlicevic (2001) for example introduce their researcher protagonists (quantitative Franz and qualitative Suzie) as representatives/prototypes of separate research cultures. They only meet at cafés and barbecues, trying hard to understand each other.

[6] The interviews took place a few weeks after follow-up, i.e. approximately 2 months after the last session/post-test and 7 months after the pre-test. This allowed me – the researcher – to calculate preliminary results of the quantitative investigation and include them in the interview. At that time, I did not regard this procedure as controversial, but later I realized that some researchers find it an inappropriate quantitative element in a qualitative method. However, the procedure allowed me to explore aspects of the participants’ experience in an interesting way. At the time of the interview not all participants had a clear memory of how their state of anxiety etc. was more than half a year before. Some of them even questioned that it could be possible to see anything out of the questionnaires. However, I was able to document a positive development in several domains with all participants. When informed about this, in the interviews, the participants readily, if slightly surprised, accepted the effect/outcome and provided detailed and rich descriptions of their therapeutic process, thus facilitating a richer interpretation also of the quantitative data and adding important participant perspectives to the study.

[7] The results of the quantitative investigations were presented to some of the oncologists I had consulted in the preliminary phase. They readily accepted the results as positive and sufficiently promising to recommend the funding of a randomized controlled trial. The funding for a RCT of receptive music therapy with ovarian cancer patients in chemotherapy was provided and a protocol was developed. This would not have been possible without the quantitative dimension of the study. The RCT study was cancelled after two years due to recruitment problems. But that’s another story….

[8] Helen Bonny, the founder of BMGIM, was also eclectic in her theoretical orientation (Bonny, 1978, Monograph #1, p. 46).

[9] The term was coined by Mary Daly in 1973 in Beyond God the Father.

References

Aigen, K. (2008a). An analysis of qualitative music therapy research reports 1987–2006: Articles and book chapters. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 35, 251-261. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2008.05.001

Aigen, K. (2008b). An analysis of qualitative music therapy research reports 1987–2006: Doctoral studies. The Arts in Psychotherapy 35,307-319. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2008.06.001

Aigen, K. (2012). An update of references in the articles 2008a and 2008b. Unpublished material at the website of the Nordic Journal of Music Therapy.

Aldridge, D. (1996). From out of the silence: Music therapy research and practice in medicine. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Ansdell, G., & Pavlicevic, M. (2001). Beginning research in the arts therapies. A practical guide. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health. How people manage stress and stay well. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Bonde, L. O. (2004). Musik als Co-Therapeutin. Gedanken zum Verhältnis zwischen Musik und Inneren Bildern in The Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music (BMGIM). In Frohne-Hagemann, Rezeptive Musiktherapie (Eds.) Theorie und Praxis [Receptive Music Therapy. Theory and Practice] (pp. 111-139). Wiesbaden, Reichert Verlag: .

Bonde, L. O. (2005a). The Bonny method of guided imagery and music (BMGIM) with cancer survivors. A psychosocial study with focus on the influence of BMGIM on mood and quality of life. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Aalborg University. Aalborg, Denmark.

Bonde, L. O. (2005b). "Finding a new place..." Metaphor and narrative in one cancer survivor's BMGIM therapy. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 14, 137-154. doi: 10.1080/08098130509478135

Bonde, L. O. (2007a). Imagery, metaphor, and perceived outcome in six cancer survivor's BMGIM therapy. In A. Meadows (Ed.), Qualitative Inquiries in Music Therapy: A Monograph Series Vol. 3 (pp. 132-164). Gilsum, NH: Barcelona.

Bonde, L.O. (2007b). Kreative Methodenintegration in der musiktherapeutischen Forschung- Reflexionen über Methodenwahl und Methodenprobleme im Forschungsprojekt »Rezeptive Musiktherapie mit Krebspatientinnen in der Rehabilitationsphase«. Musiktherapeutische Umschau 28, 93-109. doi: 10.13109/muum.2007.28.2.93

Bonde, L. O. (2007c). Music as co-therapist. Investigations and reflections on the relationship between music and imagery in the Bonny method of guided imagery and music (BMGIM). In I. Frohne-Hagemann (Ed.), Receptive Music Therapy. Theory and Practice (pp. 43-74). Wisebaden: Reichert Verlag.

Bonde, L.O. (2007d). Using multiple methods in music therapy health care research. Reflections on using multiple methods in a research project about receptive music therapy with cancer survivors. In J. Edwards (Ed.), Music: Promoting health and creating community in healthcare contexts (pp. 105-122). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Bonde, L.O. (2009). Musik og menneske. Introduktion til musikpsykologi. [Music and the human being. Introduction to the psychology of music]. Copenhagen: Samfundslitteratur.

Bonny, H.L. (2002). Music and consciousness: The evolution of guided imagery and music ( Lisa Summer, editor). Gilsum NH: Barcelona.

Bradt, J., Burns, D. S., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Mixed methods research in music therapy. Journal of Music Therapy, 50, 123-148. doi: 10.1093/jmt/50.2.123

Bruscia, K. E. (1995). Differences between quantitative and qualitative research paradigms: Implications for music therapy research. In. B. L. Wheeler (Ed.), Music therapy research: Quantitative and qualitative perspectives (pp. 65-78). Phoenixville: Barcelona Publishers.

Burns, D. S. (1999). The effect of the Bonny method of guided imagery and music on the quality of life and cortisol levels of cancer patients. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas.

Burns, D. S. (2001). The effect of the Bonny method of guided imagery and music on the mood and life quality of cancer patients. Journal of Music Therapy 38, 51-65. 1doi: 0.1093/jmt/38.1.51

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (2nd. ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Daly, M. (1973). Beyond God the Father: Toward a philosophy of women's liberation. Boston: Beacon Press.

de Vaus, D.A. (2001). Research design in social research. London: Sage.

Edwards, J. (1999). Considering the paradigmatic frame: Social science research approaches relevant to research in music therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy 26, 73-80. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4556(98)00049-5

Edwards, J. (2005). Developments and issues in music therapy research. In B. Wheeler (Ed.), Music therapy research (pp. 20-32). (2nd ed.). Gilsum NH: Barcelona Publishers.

Fayers, P., S. Weeden, Curran, D. (1998). EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference Values. Brussels: EORTC Quality of Life Study Group.

Ferrara, L. (1991). Philosophy and the analysis of music. Bridges to musical sound, form, and reference. New York: Greenwood Press.

Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A.J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14-26. doi: 10.3102/0013189X033007014

Køppe, S. (2012) A moderate eclecticism: Ontological and epistemological issues. Integr Psych Behav, 46(1), 1-19. doi: 10.1007/s12124-011-9175-6

Körlin, D., & Wrangsjö, B. (2001). Gender differences in outcome of guided imagery and music (GIM) therapy. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 10,132-143. doi: 10.1080/08098130109478027

Körlin, D., & Wrangsjö, B. (2002). Treatment effects of GIM therapy. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 11(2), 3-15. doi: 10.1080/08098130209478038

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to western thought. New York: Basic Books.

Mason, J. (1996). Qualitative researching. London: Sage.

Meetoo, D., & Temple, B. (2003). Issues in multi-method research: Constructing self-care. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2(3).

McNair, D., M. Lorr, et al. (1971). Profile of mood states. San Diego: Educational and Industrial testing Service.

Padilla, G., M. Grant, et al. (1996). Quality of life - cancer scale (QOL-CA). Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. Spilker. New York: Raven Press.

Ricoeur, P. (1978). The rule of metaphor. Multi-disciplinary studies of the creation of meaning in language. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Ricoeur, P. (1984). Time and narrative: Threefold Mimesis. Time and Narrative Vol. 1. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Ridder, H.M. (2003). Singing dialogue: Music therapy with persons in advanced stages of dementia ; A case study research design. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark.

Robson, C. (2011). Real world research. A resource for users of social research methods in applied settings. (2nd. ed.). Malden, MA : Blackwell publishing.

Robson, C. (2011). Real world research. A resource for users of social research methods in applied settings. (3rd. ed.). Chichester: Wiley.

Ruud, E. (1998). Music, health, and quality of life. Music Therapy: Improvisation, Communication, and Culture. Gilsum, NH: Barcelona Publishers.

Sale, J. E. M., L. H. Lohfeld, et al. (2002). Revisiting the Quantitative-Qualitative Debate: Implications for Mixed-Methods Research. Quality & Quantity, 36, 43-53. doi: 10.1023/A:1014301607592

Snaith, R. P. ,& Zigmond, A. S. (1994). The hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS). Manual. NFER-NELSON.

Strauss, A. L. and Corbin, J.M. (1995). Grounded theory in practice. London: Sage Publications.

Torrance, H. (2012). Triangulation, respondent validation, and democratic participation in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6, 111-123. doi: 10.1177/1558689812437185

Wärja, M., & Bonde, L.O. (2014). Music as co-therapist: Towards a taxonomy of music in therapeutic music and imagery work. Music and Medicine, 6(2), 16-27.

Wheeler, B. L. (Ed.) (1995). Music therapy research. Quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Phoenixville: Barcelona Publishers.

Wheeler, B. L. (Ed.) (2005). Music therapy research (2nd ed.). Gilsum NH: Barcelona Publishers.

Wheeler, B., & Kenny, C. (2005). Principles of qualitative research. In. B. Wheeler (Eds.), Music therapy research (2nd ed). (pp. 59-71). Gilsum NH: Barcelona Publishers.

Wheeler & Murphy, (in press). Music therapy research (3rd ed.). Gilsum NH: Barcelona Publishers.

Wigram, T., & Gold, C. (2012). The religion of evidence-based practice: Helpful or harmful to health and wellbeing? In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & D. Miell (Eds), Music, Health and Wellbeing (pp. 164-182). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199586974.003.0013

Wigram, T., Nygaard Pedersen, I. & Bonde, L.O. (2002). A comprehensive guide to music therapy theory, clinical practice, research and training. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.