Special Section: In Memory of Clive Robbins 1927-2011

Thank You, Clive

By Alan Turry

I had already been working in the field for 10 years as a clinical improviser when I began my direct relationship with Clive Robbins. I already felt as if I had a relationship with Clive. Similar to many other music therapists, I had already heard the work of Nordoff and Robbins. Many of us were inspired by the powerful, moving audio excerpts from their sessions. When I heard the soulful and creative musical interaction, I felt immediately that was what I wanted to do. I actually did much of my clinical improvising work on guitar and in groups, but I also utilized piano and thought I had a deep understanding of the way in which Nordoff and Robbins worked. Barbara Hesser, who designed and directed the music therapy program at NYU had cultivated a deep appreciation for the work of Nordoff and Robbins and many of us who trained and taught at NYU felt we were in some sense carrying on the tradition.

What struck me right away when I began to work with Clive was how much I had to learn from him. Although we think of him as co-therapist—the person "on the floor" in NR lingo—and not the primary music maker in sessions, he actually knew so much about music. Extremely sensitive to the subtle nuances in the musical interaction, Clive appeared to have a physiological reaction to musical forms, shuddering with the sounds he heard. He immersed himself in the excerpts he analyzed, and was able to talk about all the elements of music effortlessly. He could identify different scales and idioms, and had an impressive memory for what took place between Nordoff and a client so many years previously. He also seemed to listen to the sessions he had heard so many times before as if he was hearing them for the first time. He was an active and sensitive listener. He had energy, passion, intensity, and total commitment to what he was listening to and what he was trying to convey.

I am grateful to have been able to teach with Clive. He was an inspirational and perceptive teacher who adjusted his lecture in response to how the students were engaging with the content of his talk, just as he worked in therapy. As much as the content, Clive’s emotional tone left a lasting impression on students. He was not afraid to convey his love - what he called "active love" for his clients, and this was so attractive to students who wanted to approach the work with the same loving attitude. He was also extremely eloquent in describing the creative process, connecting it to his own philosophical and spiritual ideas based on Anthroposophy. He had a way of combining emotional expression with intellectual clarity that captured the students’ imagination. He also had a way of sensing what individual students needed to hear and geared his lectures to address those points. Frequently after a lecture a student would come up to him and share that he was talking directly to him or her when he was making a general point about the work. Clive was able to motivate students and inspire them to believe that as they became more authentic, more true to their creative and musical self, they would become more successful as clinical musicians.

It was a gift to be around Clive for such a long period of time. I had the good fortune of working with Clive for over 20 years at the Nordoff-Robbins Center at New York University. This was the place where Clive spent more of his professional life than anywhere else. I heard his accent change from the precise British inflection to an American one tinged with New York-ese—he enjoyed using Yiddish words when speaking to New York audiences. He constantly spoke of how he loved the up-tempo pace and creative freedom and diversity of the City and loved to tell people that the Center was a few blocks away from Broadway. He identified a particular style used by therapists as "Broadway heroic"— which he said tongue in cheek, because he clearly loved music from Broadway and recognized the potential effectiveness of this kind of music in therapy. In fact Clive was always open to hearing a new contemporary style that could be effective in sessions.

Clive had the vision and freedom to support innovations. Although Paul Nordoff was a concertizing classical pianist and the requirements of the training were a level of proficiency in the classical tradition on piano, Clive embraced therapists whose authentic improvising grew out contemporary styles such as jazz and guitarists of various backgrounds including electric rock and loved training them. He loved to learn from students. He was always willing to look at things from a different perspective and cultivated a sense of freedom among all of us who worked with him.

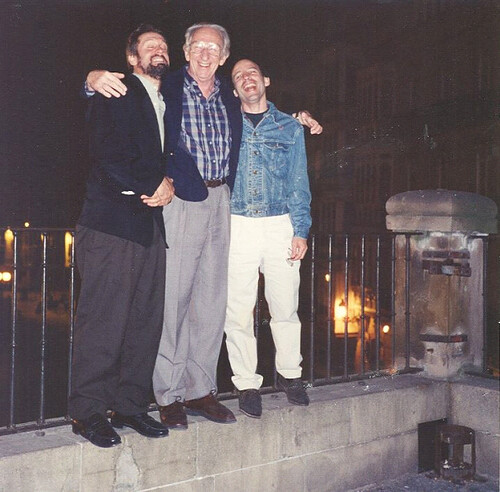

Clive was a mentor to me in many ways. He introduced me proudly to Dover sole when we traveled together to London. When we walked through Hampstead Heath to teach at the London Centre he would point out various landscapes. He had a sensitive visual eye from his days as an artist. As we travelled together to the various Nordoff-Robbins sites around the world he would point out qualities in the clinical work he wanted me to be particularly aware of. He recognized that each facility had a character reflective of its national character, and felt that it was important to share and learn and integrate the various qualities.

When we taught in Asia Clive shared his awareness of and sensitivity to how cultural norms had an effect on a student’s capacity to embrace the creative approach of Nordoff-Robbins music therapy. It was immensely exciting to see Clive’s impact on audiences in Asia. This elder statesman, a pioneer, acted so playful and free as he lectured, conveying acceptance and playfulness. He drew so many to him, and was such an important person in helping the field of music therapy to expand in countries like Japan and Korea. Students wanted to embrace their own creativity, their own authenticity, and Clive became a kind of idealized father figure who held out the promise that it would be possible. I believe Clive felt he had a mission to bring these values of creativity and freedom to these cultures that he felt needed it most. We would often debate-sometimes quite heatedly- about cultural stereotypes and how to approach teaching students from various cultures.

In the same way that Clive learned from accepting new kinds of musicians into the training program, he learned from his colleagues and peers at NYU in terms of integrating concepts of music psychotherapy. This is a term that describes the fact that the program integrates relationship dynamics and unconscious motivations as an integral part of being a successful improviser. Clive was always open, yet he was uncomfortable with the term music psychotherapy as he felt that it implied that music was secondary to the process of psychotherapy. He was much more simpatico with a term he coined—psychotherapy in music—that music making contained within it the seeds of psychological change. He enjoyed professional discourse and facilitated a sense of excitement when discussing ideas. We would all look forward to hearing his next theory, seeing his new diagram. He was able to integrate ideas from various disciplines and integrate them into his own thinking and teaching seamlessly. I felt privileged working alongside Clive and Ken Aigen, as we could often engage in spontaneous discussion about the work that would trigger a new conceptualization.

Because of Clive’s physical disability (he could not use his left hand for fine motor tasks due to an injury to his shoulder) he had an intimate sensitivity when working with those with the same type of physical challenges. And because of Clive’s own willingness to break the rules, to think outside the box, he could approach challenging behaviors with a positive attitude, understanding and accepting that a new development could grow out of the situation.

Clive had many partners throughout his professional career. He was a great collaborator, and his ability to partner with a wide variety of people with such different personalities reveals his flexible and richly complex personality. He could be a supporter, a leader, firm and direct, quiet and tender depending on the needs of the client and the balance between him and his partner. With Paul Nordoff, he was often quietly guiding the client while sensing the direction of Paul’s musical interventions. Carol Robbins often functioned as the stable anchor that allowed Clive to take the lead in sessions and create musical ideas and take clinical leadership.

Even at the end of his life when his enormous energy was sapped because of illness, he was driven to continue to travel and teach. And on occasion, he would come into a session and find ways of reaching difficult to reach children by being himself. He could still access his childlike playful creativity at 83 years old—it was amazing to see. In one of the last sessions he did, a child with autism who had not been responding for several weeks noticed that Clive was in the room yet did not become an active participant in the session. Clive slowly, with great deliberation, moved closer and closer to the wind chimes, until his nose actually crossed over to the side of the wind chime that the child was on. The boy smiled, and began to move closer and play. It was classic Clive, and it was a turning point that helped the boy become more engaged and responsive in subsequent sessions.

Clive Robbins was—it is not possible to write was—Clive Robbins is, and will continue to be, an example of love in action. Thank you, Clive, for your leadership and inspiration.