Special Section: In Memory of Clive Robbins 1927-2011

"In the Spirit": Invited Editorial

By Kenneth Aigen

It is an impossible task to capture any man’s life in words, much less a man like Clive Robbins, whose adult life alone had four phases that were remarkably different from one another. In reading each of the nine articles about Clive you will learn about his different facets. For those of you who knew Clive personally, some of these facets will be very familiar and some others will be new to you. For those readers who did not have a personal relationship with Clive, you will feel like you have one when you complete these readings.

As you work your way through these varied pieces, a number of repeated themes will come out. I would like to highlight nine of them, because these themes really do encapsulate much of what Clive was as a music therapist, as a man, and as a human being.

You will see that through the years, (i) Clive kept correspondence with many people all over the world, maintaining contact with them with a keen interest in helping them to further their own development. The connection Clive made with people carried with it a life-long nurturance, mentorship, and colleagueship. (ii) Related to this bond was the way that Clive encouraged change, innovation, and the adaptation of Nordoff-Robbins music therapy to local conditions and new influences, but in a way that maintained its core. He solved the riddle that is the basic challenge of life and all movements/ideologies/philosophies: this how to keep the core of a message and insight while allowing its natural evolution to occur. He knew how to maintain its identity within change and evolution and it was his generosity of spirit—which was manifested in countless ways—that was the key to this ability.

Clive really did approach life with (iii) a spirit of adventure. Improvisation as a clinical vehicle suited him well because he constantly jumped into the unknown in his own life. His ongoing refrain to all students facing a block or fear was “Make the growth choice!”, which was understood to mean facing your fears and going beyond them. Of course he was able to motivate people in this regard because (iv) it was always done with a strongly felt spirit of love that was the foundation of all of Clive’s interactions with his fellow human beings.

Two things that seem diametrically opposed to one another but that are actually strongly related are (v) Clive’s enjoyment of life (including serious imbibing of his favorite spirits, which of course varied according to what country he was in!) and (vi) Clive’s complete and utter devotion to work and to The Work. (The former construct referring to the common conception of the word and the latter construct to the shared effort in which all music therapists working in a creative and improvisational ways were engaged.) Clive loved to drink and socialize, and yet I never met a person whose waking hours were more filled with work than Clive. He loved to work, he loved to enjoy life, and he felt strongly that work should be enjoyable.

Related to the work-play dichotomy was Clive’s (vii) unique melding of the practical and the spiritual. In some ways, he had a very grounded spirituality and he was as focused on the details of concrete reality as on grand visionary ideas. Each one gave the other meaning—without a focus on the “nuts and bolts” you couldn’t get to the sublime.

Clive was also (viii) a lover of stories and myths and was a fine story teller with a speaking voice that moved people. His wisdom was perceived through the tone and sonority of his voice and the way that his manner of speaking revealed more profound levels of meaning in words we may have heard before. This (ix) ability to reveal profundity was an important gift of Clive’s that drew many people to him. He could clearly communicate—in his words and in his overall being—that music and music therapy held the profoundest implications for understanding the meaning of human life.

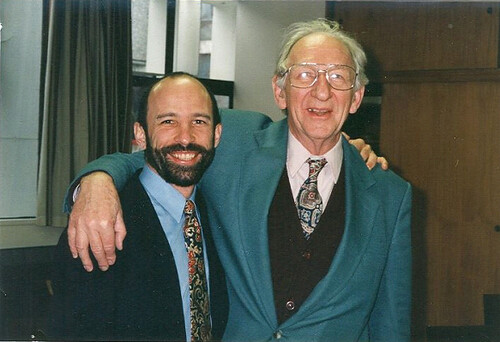

Clive and I were very compatible, both in temperament and in intellect. One of the great joys of my life was the five-week trip we took together throughout Japan, Australia, and New Zealand in the summer of 1997. The photograph accompanying this editorial is from that trip and I can see in my own face a radiance that was infused by the opportunity to work so closely with Clive for an extended period.

However, one area in which we were quite different was in the area of esoteric and spiritual belief systems. He knew that I did not share his faith in phenomena such as reincarnation and communicating with extra-human spirits of various types, yet our mutual respect was so great that this area of difference did not diminish our relationship and affection for each other; it was something that we both acknowledged and that, in some ways, even enriched our relationship. Sometimes when you have fundamental differences with a person, it makes the areas of connection that much stronger.

So one day in the early 2000s, Clive walked into my office with a mixture of excitement, a mischievous glint in his eye, and about half a dozen copies of a book titled In the Spirit: Conversations with the Spirit of Jerry Garcia. Clive was well aware of my strong affinity for Jerry Garcia, lead guitarist of the Grateful Dead. This book was written by Wendy Weir, the sister of Bob Weir, the rhythm guitarist of the band. The book recounted three years of conversations that the author reported having with the spirit of Jerry Garcia after his death in 1995. Clive liked to treat humorously what I knew he felt was my overly rational worldview that did not allow for the types of beliefs that were central to his own life. And I could see he was taking great pleasure in the fact that one of the touchstone figures in my life was now playing a central role in a drama concerning the world of the spirit.

I was drawn to this book today as I was reflecting on what to write in this editorial. I opened the book and came to a page where the author poses a question to Garcia’s spirit: “What message would you like to give?” Here is the reply:

One of love. I cannot say this enough. . . . Many of you have felt great pain and grief in my passing. This is a gift I have given you. Through the pain you have been able to search deeply within and release that love that radiates from your true self. You have reaffirmed your sense of self and sense of community. . . . The music is the vehicle for this love. Its energy, its vibration, breaks through the subtle barriers of human consciousness to free our inner selves, to give us the opportunity to discover who we truly are. (Weir, 1999, pp. 80-81)

Clive truly felt that music is the vehicle for a fully human life. One of the ideas that he was enamored with in the last ten years of his life was adapted from the writings of Victor Zuckerkandl: this was the concept of homo musicus, man as musician, the being that requires music to realize itself fully. Many of us are heartbroken over the loss of Clive, and while Clive would have sympathy for our pain, he would simply say, “Get to work!” Get to the work of mediating the relationship to music for which our clients, indeed all people, long. It’s likely that Clive saw himself as a vehicle, a medium, a tool to facilitate the development and evolution of all people in a way that could only happen through music. We would like to present the following reminiscences to you in the spirit. That is, in a way that they will inspire you to continue the work to which Clive dedicated his life.

Reference

Weir, W. (1999). In the spirit: Conversations with the spirit of Jerry Garcia. New York: Three Rivers Press.